The Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest and west of England, the West Midlands, and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran its first trains in 1838. It was engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who chose a broad gauge of 7 ft (2,134 mm)—later slightly widened to 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm)—but, from 1854, a series of amalgamations saw it also operate 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard-gauge trains; the last broad-gauge services were operated in 1892.

The GWR was the only company to keep its identity through the Railways Act 1921, which amalgamated it with the remaining independent railways within its territory, and it was finally merged at the end of 1947 when it was nationalised and became the Western Region of British Railways.

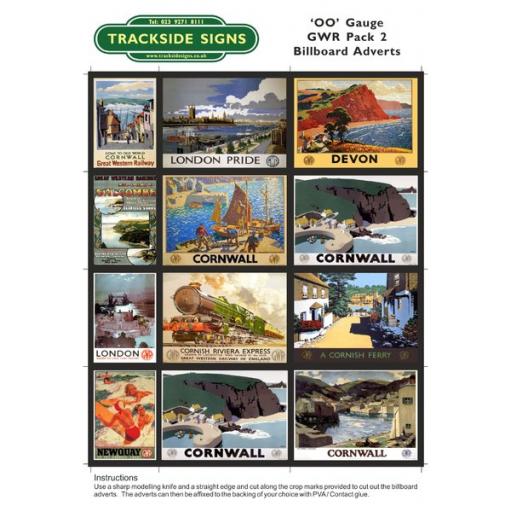

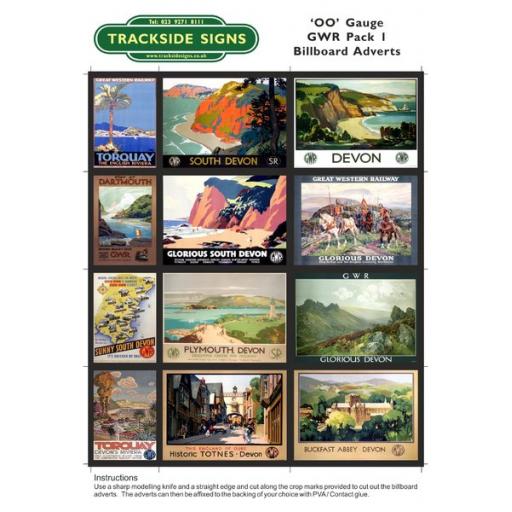

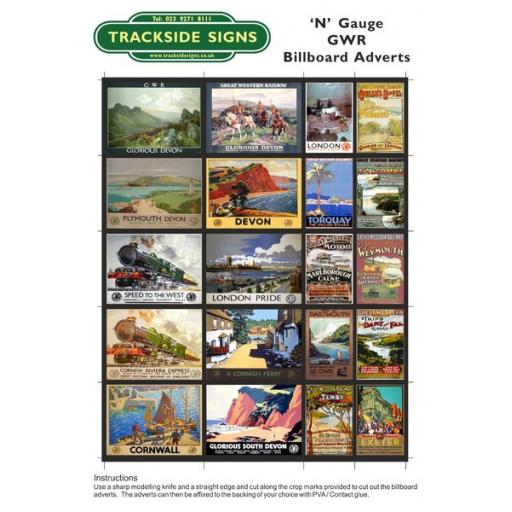

The GWR was called by some "God's Wonderful Railway" and by others the "Great Way Round" but it was famed as the "Holiday Line", taking many people to English and Bristol Channel resorts in the West Country as well as the far southwest of England such as Torquay in Devon, Minehead in Somerset, and Newquay and St Ives in Cornwall. The company's locomotives, many of which were built in the company's workshops at Swindon, were painted a Brunswick green colour while, for most of its existence, it used a two-tone "chocolate and cream" livery for its passenger coaches. Goods wagons were painted red but this was later changed to mid-grey.

Great Western trains included long-distance express services such as the Flying Dutchman, the Cornish Riviera Express and the Cheltenham Spa Express. It also operated many suburban and rural services, some operated by steam railmotors or autotrains. The company pioneered the use of larger, more economic goods wagons than were usual in Britain. It operated a network of road motor (bus) routes, was a part of the Railway Air Services, and owned ships, docks and hotels.

The Great Western Railway originated from the desire of Bristol merchants to maintain their city as the second port of the country and the chief one for American trade. The increase in the size of ships and the gradual silting of the River Avon had made Liverpool an increasingly attractive port, and with a Liverpool to London rail line under construction in the 1830s Bristol's status was threatened. The answer for Bristol was, with the co-operation of London interests, to build a line of their own; a railway built to unprecedented standards of excellence to out-perform the lines being constructed to the North West of England.

The company was founded at a public meeting in Bristol in 1833 and was incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1835. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, then aged twenty-nine, was appointed engineer.

Route of the line

This was by far Brunel's largest contract to date. He made two controversial decisions. Firstly, he chose to use a broad gauge of 7 ft (2,134 mm) to allow for the possibility of large wheels outside the bodies of the rolling stock which could give smoother running at high speeds. Secondly, he selected a route, north of the Marlborough Downs, which had no significant towns but which offered potential connections to Oxford and Gloucester. This meant the line was not direct from London to Bristol. From Reading heading west, the line would curve in a northerly sweep back to Bath.

Brunel surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself, with the help of many, including his solicitor Jeremiah Osborne of Bristol law firm Osborne Clarke who on one occasion rowed Brunel down the River Avon himself to survey the bank of the river for the route.

George Thomas Clark played an important role as an engineer on the project, reputedly taking the management of two divisions of the route including bridges over the River Thames at Lower Basildon and Moulsford and of Paddington Station. Involvement in major earth-moving works seems to have fed Clark's interest in geology and archaeology and he, anonymously, authored two guidebooks on the railway: one illustrated with lithographs by John Cooke Bourne; the other, a critique of Brunel's methods and the broad gauge.

The first 22+1⁄2 miles (36 km) of line, from Paddington station in London to Maidenhead Bridge station, opened on 4 June 1838. When Maidenhead Railway Bridge was ready the line was extended to Twyford on 1 July 1839 and then through the deep Sonning Cutting to Reading on 30 March 1840. The cutting was the scene of a railway disaster two years later when a goods train ran into a landslip; ten passengers who were travelling in open trucks were killed.

This accident prompted Parliament to pass the 1844 Railway Regulation Act requiring railway companies to provide better carriages for passengers. The next section, from Reading to Steventon crossed the Thames twice and opened for traffic on 1 June 1840. A 7+1⁄4-mile (12 km) extension took the line to Faringdon Road on 20 July 1840. Meanwhile, work had started at the Bristol end of the line, where the 11+1⁄2-mile (19 km) section to Bath opened on 31 August 1840.

On 17 December 1840, the line from London reached a temporary terminus at Wootton Bassett Road west of Swindon and 80.25 miles (129 km) from Paddington. The section from Wootton Bassett Road to Chippenham was opened on 31 May 1841, as was Swindon Junction station where the Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway (C&GWUR) to Cirencester connected. That was an independent line worked by the GWR, as was the Bristol and Exeter Railway (B&ER), the first section of which from Bristol to Bridgwater was opened on 14 June 1841. The GWR main line remained incomplete during the construction of the 1-mile-1,452-yard (2.94 km) Box Tunnel, which was ready for trains on 30 June 1841, after which trains ran the 152 miles (245 km) from Paddington through to Bridgwater. In 1851, the GWR purchased the Kennet and Avon Canal, which was a competing carrier between London, Reading, Bath and Bristol.

The GWR was closely involved with the C&GWUR and the B&ER and with several other broad-gauge railways. The South Devon Railway was completed in 1849, extending the broad gauge to Plymouth, whence the Cornwall Railway took it over the Royal Albert Bridge and into Cornwall in 1859 and, in 1867, it reached Penzance over the West Cornwall Railway which originally had been laid in 1852 with the 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge or "narrow gauge" as it was known at the time. The South Wales Railway had opened between Chepstow and Swansea in 1850 and became connected to the GWR by Brunel's Chepstow Bridge in 1852. It was completed to Neyland in 1856, where a transatlantic port was established.

There was initially no direct line from London to Wales as the tidal River Severn was too wide to cross. Trains instead had to follow a lengthy route via Gloucester, where the river was narrow enough to be crossed by a bridge. Work on the Severn Tunnel had begun in 1873, but unexpected underwater springs delayed the work and prevented its opening until 1886.

Brunel's 7-foot gauge and the "gauge war"

See also: Gauge War, London and South Western Railway § Gauge wars, Isambard Kingdom Brunel § Great Western Railway, and List of GWR broad gauge locomotives

Brunel had devised a 7 ft (2,134 mm) track gauge for his railways in 1835. He later added 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm), probably to reduce friction of the wheel sets in curves. This became the 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) broad gauge. Either gauge may be referred to as "Brunel's" gauge.

In 1844, the broad-gauge Bristol and Gloucester Railway had opened, but Gloucester was already served by the 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge lines of the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway. This resulted in a break of gauge that forced all passengers and goods to change trains if travelling between the south-west and the North. This was the beginning of the "gauge war" and led to the appointment by Parliament of a Gauge Commission, which reported in 1846 in favour of standard gauge so the 7-foot gauge was proscribed by law (Regulating the Gauge of Railways Act) except for the southwest of England and Wales where connected to the GWR network.

Other railways in Britain were to use standard gauge. In 1846 the Bristol and Gloucester was bought by the Midland Railway and it was converted to standard gauge in 1854, which brought mixed-gauge track to Temple Meads station – this had three rails to allow trains to run on either broad or standard gauge.

The GWR extended into the West Midlands in competition with the Midland and the London and North Western Railway. Birmingham was reached through Oxford in 1852 and Wolverhampton in 1854. This was the furthest north that the broad gauge reached. In the same year the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway and the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway both amalgamated with the GWR, but these lines were standard gauge, and the GWR's own line north of Oxford had been built with mixed gauge.

This mixed gauge was extended southwards from Oxford to Basingstoke at the end of 1856 and so allowed through goods traffic from the north of England to the south coast (via the London and South Western Railway – LSWR) without transshipment.

The line to Basingstoke had originally been built by the Berks and Hants Railway as a broad-gauge route in an attempt to keep the standard gauge of the LSWR out of Great Western territory but, in 1857, the GWR and LSWR opened a shared line to Weymouth on the south coast, the GWR route being via Chippenham and a route initially started by the Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth Railway. Further west, the LSWR took over the broad-gauge Exeter and Crediton Railway and North Devon Railway, also the standard-gauge Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway.

It was several years before these remote lines were connected with the parent LSWR system and any through traffic to them was handled by the GWR and its associated companies.

By now the gauge war was lost and mixed gauge was brought to Paddington in 1861, allowing through passenger trains from London to Chester. The broad-gauge South Wales Railway amalgamated with the GWR in 1862, as did the West Midland Railway, which brought with it the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway, a line that had been conceived as another broad-gauge route to the Midlands but which had been built as standard gauge after several battles, both political and physical.

On 1 April 1869, the broad gauge was taken out of use between Oxford and Wolverhampton and from Reading to Basingstoke. In August, the line from Grange Court to Hereford was converted from broad to standard and the whole of the line from Swindon through Gloucester to South Wales was similarly treated in May 1872. In 1874, the mixed gauge was extended along the main line to Chippenham and the line from there to Weymouth was narrowed. The following year saw mixed gauge laid through the Box Tunnel, with the broad gauge now retained only for through services beyond Bristol and on a few branch lines.

The Bristol and Exeter Railway amalgamated with the GWR on 1 January 1876. It had already made a start on mixing the gauge on its line, a task completed through to Exeter on 1 March 1876 by the GWR. The station here had been shared with the LSWR since 1862. This rival company had continued to push westwards over its Exeter and Crediton line and arrived in Plymouth later in 1876, which spurred the South Devon Railway to also amalgamate with the Great Western. The Cornwall Railway remained a nominally independent line until 1889, although the GWR held a large number of shares in the company.

One final new broad-gauge route was opened on 1 June 1877, the St Ives branch in west Cornwall, although there was also a small extension at Sutton Harbour in Plymouth in 1879. Part of a mixed gauge point remains at Sutton Harbour, one of the few examples of broad gauge trackwork remaining in situ anywhere.

Once the GWR was in control of the whole line from London to Penzance, it set about converting the remaining broad-gauge tracks. The last broad-gauge service left Paddington station on Friday, 20 May 1892; the following Monday, trains from Penzance were operated by standard-gauge locomotives.

Into the 20th century

After 1892, with the burden of operating trains on two gauges removed, the company turned its attention to constructing new lines and upgrading old ones to shorten the company's previously circuitous routes. The principal new lines opened were:

The generally conservative GWR made other improvements in the years before the World War I such as restaurant cars, better conditions for third class passengers, steam heating of trains, and faster express services. These were largely at the initiative of T. I. Allen, the Superintendent of the Line and one of a group of talented senior managers who led the railway into the Edwardian era: Viscount Emlyn (Earl Cawdor, Chairman from 1895 to 1905); Sir Joseph Wilkinson (general manager from 1896 to 1903), his successor, the former chief engineer Sir James Inglis; and George Jackson Churchward (the Chief Mechanical Engineer). It was during this period that the GWR introduced road motor services as an alternative to building new lines in rural areas, and started using steam rail motors to bring cheaper operation to existing branch lines.

One of the "Big Four"

See also: List of constituents of the Great Western Railway

1923 saw the construction of the first of 171 Castle Class locomotives

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the GWR was taken into government control, as were most major railways in Britain. Many of its staff joined the armed forces and it was more difficult to build and maintain equipment than in peacetime. After the war, the government considered permanent nationalisation but decided instead on a compulsory amalgamation of the railways into four large groups. The GWR alone preserved its name through the "grouping", under which smaller companies were amalgamated into four main companies in 1922 and 1923.

The new Great Western Railway had more routes in Wales, including 295 miles (475 km) of former Cambrian Railways lines and 124 miles (200 km) from the Taff Vale Railway. A few independent lines in its English area of operations were also added, notably the Midland and South Western Junction Railway, a line previously working closely with the Midland Railway but which now gave the GWR a second station at Swindon, along with a line that carried through-traffic from the North via Cheltenham and Andover to Southampton.

The 1930s brought hard times but the company remained in fair financial health despite the Depression. The Development (Loans, Guarantees and Grants) Act 1929 allowed the GWR to obtain money in return for stimulating employment and this was used to improve stations including London Paddington, Bristol Temple Meads and Cardiff General; to improve facilities at depots and to lay additional tracks to reduce congestion. The road motor services were transferred to local bus companies in which the GWR took a share but instead, it participated in air services.

A legacy of the broad gauge was that trains for some routes could be built slightly wider than was normal in Britain and these included the 1929-built "Super Saloons" used on the boat train services that conveyed transatlantic passengers to London in luxury. When the company celebrated its centenary during 1935, new "Centenary" carriages were built for the Cornish Riviera Express, which again made full use of the wider loading gauge on that route.

World War II and after

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the GWR returned to direct government control, and by the end of the war a Labour government was in power and again planning to nationalise the railways. After a couple of years trying to recover from the ravages of war, the GWR became the Western Region of British Railways on 1 January 1948. The Great Western Railway Company continued to exist as a legal entity for nearly two more years, being formally wound up on 23 December 1949.

GWR designs of locomotives and rolling stock continued to be built for a while and the region maintained its own distinctive character, even painting for a while its stations and express trains in a form of chocolate and cream.

About 40 years after nationalisation British Rail was privatised and the old name was revived by Great Western Trains, the train operating company providing passenger services on the old GWR routes to South Wales and the South West, which subsequently became First Great Western as part of the FirstGroup but in September 2015 changed its name to Great Western Railway in order to 'reinstate the ideals of our founder'. The operating infrastructure, however, was transferred to Railtrack and has since passed to Network Rail. These companies have continued to preserve appropriate parts of its stations and bridges so historic GWR structures can still be recognised around the network.