British Rail

British Railways (BR), which from 1965 traded as British Rail, was the state-owned company that operated the national rail system rail transport in Great Britain between 1948 and 1997. It was formed from the nationalisation of the Big Four British railway companies and lasted until the gradual privatisation of British Rail, in stages between 1994 and 1997. Originally a trading brand of the Railway Executive of the British Transport Commission, it became an independent statutory corporation in January 1963, when it was formally renamed the British Railways Board.

The period of nationalisation saw sweeping changes in the railway. A process of dieselisation and electrification took place, and by 1968 steam locomotives had been entirely replaced by diesel and electric traction, except for the Vale of Rheidol Railway (a narrow-gauge tourist line). Passengers replaced freight as the main source of business, and one third of the network was closed by the Beeching cuts of the 1960s in an effort to reduce rail subsidies.

On privatisation, responsibility for track, signalling and stations was transferred to Railtrack (which was later brought under public control as Network Rail) and that for trains to the train operating companies.

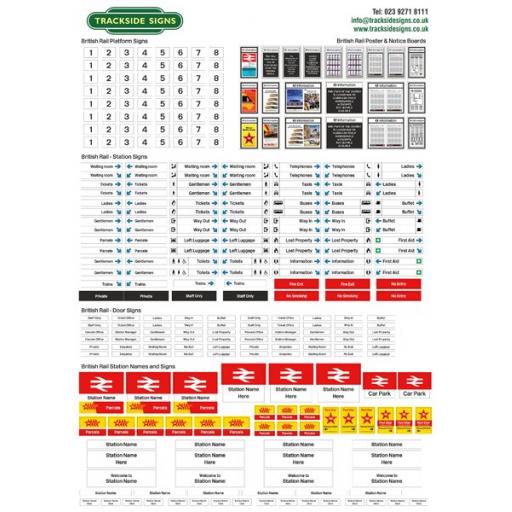

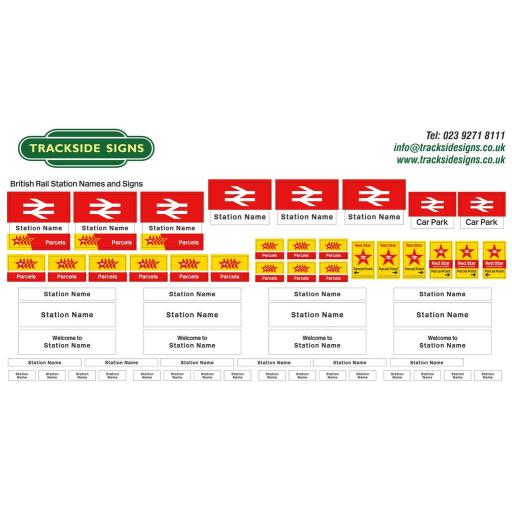

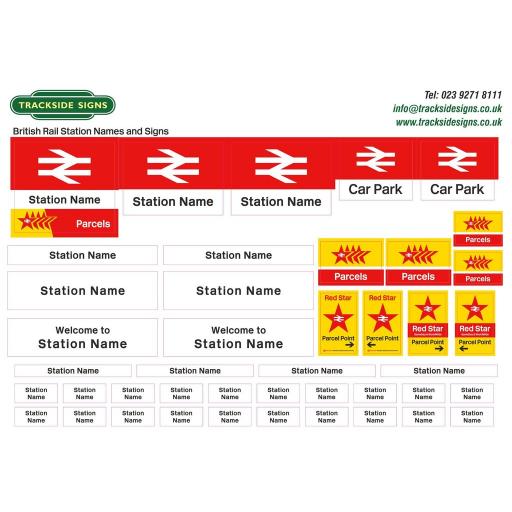

The British Rail Double Arrow logo was formed of two interlocked arrows showing the direction of travel on a double track railway and was nicknamed "the arrow of indecision". It is now employed as a generic symbol on street signs in Great Britain denoting railway stations, and as part of the Rail Delivery Group's (RDG) jointly managed National Rail brand is still printed on railway tickets.

1955 Modernisation Plan

1955 Modernisation Plan

The report, latterly known as the "Modernisation Plan", was published in January 1955. It was intended to bring the railway system into the 20th century. A government White Paper produced in 1956 stated that modernisation would help eliminate BR's financial deficit by 1962, but the figures in both this and the original plan were produced for political reasons and not based on detailed analysis. The aim was to increase speed, reliability, safety, and line capacity through a series of measures that would make services more attractive to passengers and freight operators, thus recovering traffic lost to the roads.

Important areas included:

The government appeared to endorse the 1955 programme (costing £1.2 billion), but did so largely for political reasons. This included the withdrawal of steam traction and its replacement by diesel (and some electric) locomotives. Not all the modernisations would be effective at reducing costs. The dieselisation programme gave contracts primarily to British suppliers, who had limited experience of diesel locomotive manufacture, and rushed commissioning based on an expectation of rapid electrification; this resulted in numbers of locomotives with poor designs, and a lack of standardisation. At the same time, containerised freight was being developed. The marshalling yard building programme was a failure, being based on a belief in the continued viability of wagon-load traffic in the face of increasingly effective road competition, and lacking effective forward planning or realistic assessments of future freight. A 2002 documentary broadcast on BBC Radio 4 blamed the 1950s decisions for the "beleaguered" condition of the railway system at that time.

The Beeching reports

Beeching cuts

During the late 1950s, railway finances continued to worsen, whilst passenger numbers grew after restoring many services reduced during the war, and in 1959 the government stepped in, limiting the amount the BTC could spend without ministerial authority. A White Paper proposing reorganisation was published in the following year, and a new structure was brought into effect by the Transport Act 1962. This abolished the commission and replaced it by several separate boards. These included a British Railways Board, which took over on 1 January 1963.

Following semi-secret discussions on railway finances by the government-appointed Stedeford Committee in 1961, one of its members, Dr Richard Beeching, was offered the post of chairing the BTC while it lasted, and then becoming the first Chairman of the British Railways Board.

A major traffic census in April 1961, which lasted one week, was used in the compilation of a report on the future of the network. This report—The Reshaping of British Railways—was published by the BRB in March 1963. The proposals, which became known as the Beeching cuts, were dramatic. A third of all passenger services and more than 4,000 of the 7,000 stations would close. Beeching, who is thought to have been the author of most of the report, set out some dire figures. One third of the network was carrying just 1% of the traffic. Of the 18,000 passenger coaches, 6,000 were said to be used only 18 times a year or less. Although maintaining them cost between £3m and £4m a year, they earned only about £0.5m.

Most of the closures were carried out between 1963 and 1970 (including some which were not listed in the report) while other suggested closures were not carried out. The closures were heavily criticised at the time. A small number of stations and lines closed under the Beeching programme have been reopened, with further reopenings proposed.

A second Beeching report, "The Development of the Major Trunk Routes", followed in 1965. This did not recommend closures as such, but outlined a "network for development". The fate of the rest of the network was not discussed in the report.

Post-Beeching

The basis for calculating passenger fares changed in 1964. In future, fares on some routes—such as rural, holiday and commuter services—would be set at a higher level than on other routes; previously, fares had been calculated using a simple rate for the distance travelled, which at the time was 3d per mile second class, and 4½d per mile first class (equivalent to £0.26 and £0.38 respectively, in 2019).

In 1966, a "Whites only" recruitment policy for guards at Euston station was dropped after the case of Asquith Xavier, a migrant from Dominica, who had been refused promotion on those grounds, was raised in Parliament and taken up by the then Secretary of State for Transport, Barbara Castle.

Passenger levels decreased steadily from 1962 to the late 1970s, and reached a low in 1982.[27] Network improvements included completing electrification of the Great Eastern Main Line from London to Norwich between 1976 and 1986 and the East Coast Main Line from London to Edinburgh between 1985 and 1990. A main line route closure during this period of relative network stability was the 1500 V DC-electrified Woodhead line between Manchester and Sheffield: passenger service ceased in 1970 and goods in 1981.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the closure of some railways which had survived the Beeching cuts a generation earlier, but which had seen passenger services withdrawn. This included the bulk of the Chester and Connah's Quay Railway in 1992, the Brierley Hill to Walsall section of the South Staffordshire line in 1993, while the Birmingham to Wolverhampton section of the Great Western Railway was closed in three phases between 1972 and 1992.

A further British Rail report, from a committee chaired by Sir David Serpell, was published in 1983. The Serpell Report made no recommendations as such, but did set out various options for the network including, at their most extreme, a skeletal system of less than 2000 route km. This report was not welcomed, and the government decided to quietly leave it on the shelf. Meanwhile, BR was gradually reorganised, with the regional structure finally being abolished and replaced with business-led sectors. This process, known as "sectorisation", led to far greater customer focus, but was cut short in 1994 with the splitting up of BR for privatisation.

Upon sectorisation in 1982, three passenger sectors were created: InterCity, operating principal express services; London & South East (renamed Network SouthEast in 1986) operating commuter services in the London area; and Provincial (renamed Regional Railways in 1989) responsible for all other passenger services.[28] In the metropolitan counties local services were managed by the Passenger Transport Executives. Provincial was the most subsidised (per passenger km) of the three sectors; upon formation, its costs were four times its revenue. During the 1980s British Rail ran the Rail Riders membership club aimed at 5- to 15-year-olds.

Because British Railways was such a large operation, running not just railways but also ferries, steamships and hotels, it has been considered difficult to analyse the effects of nationalisation.

Prices rose quickly in this period, rising 108% in real terms from 1979 to 1994, as prices rose by 262% but RPI only increased by 154% in the same time.

Branding

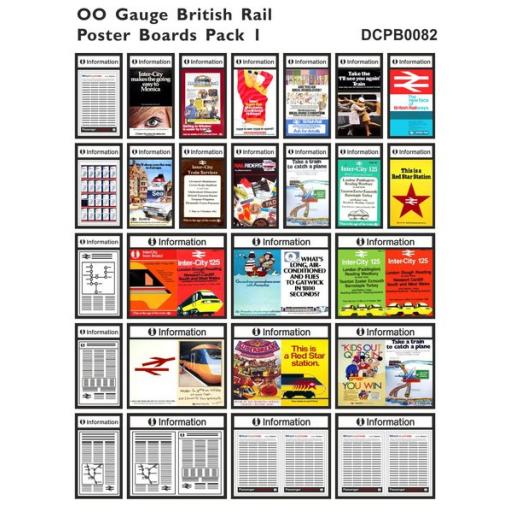

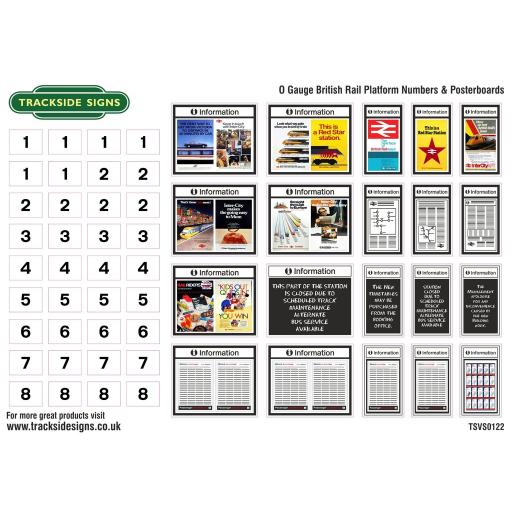

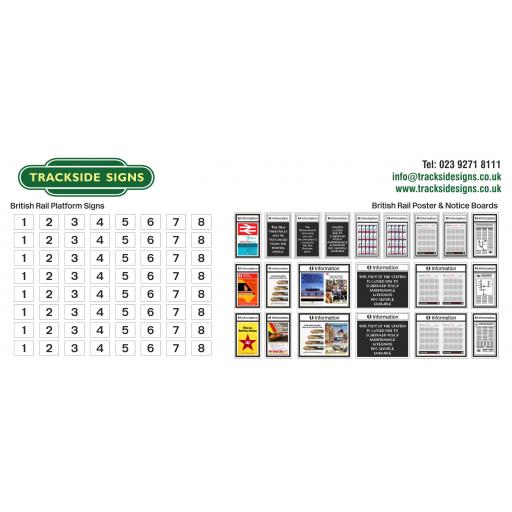

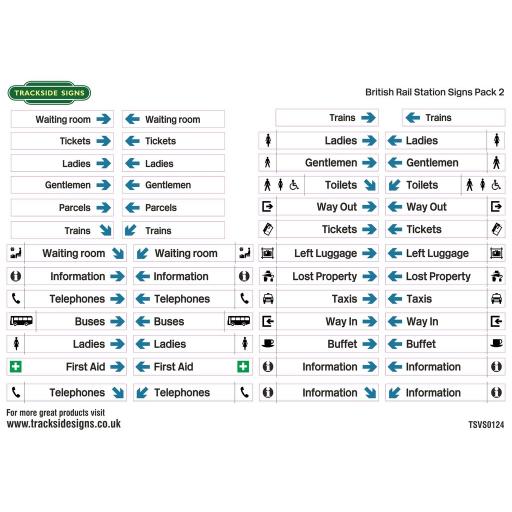

British Rail corporate liveries

1960s

The zeal for modernisation in the Beeching era drove the next rebranding exercise, and BR management wished to divest the organisation of anachronistic, heraldic motifs and develop a corporate identity to rival that of London Transport. BR's design panel set up a working party led by Milner Gray of the Design Research Unit. They drew up a Corporate Identity Manual which established a coherent brand and design standard for the whole organisation, specifying Rail Blue and pearl grey as the standard colour scheme for all rolling stock; Rail Alphabet as the standard corporate typeface, designed by Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert; and introducing the now-iconic corporate Identity Symbol of the Double Arrow logo. Designed by Gerald Barney (also of the DRU), this arrow device was formed of two interlocked arrows across two parallel lines, symbolising a double track railway. It was likened to a bolt of lightning or barbed wire, and also acquired a nickname: "the arrow of indecision". A mirror image of the double arrow was used on the port side of BR-owned Sealink ferry funnels. The new BR corporate identity and Double Arrow were rolled out in 1965, and the brand name of the organisation was truncated to "British Rail".

Post-1960s

The uniformity of BR branding continued until the process of sectorisation was introduced in the 1980s. Certain BR operations such as Inter-City, Network SouthEast, Regional Railways or Railfreight began to adopt their own identities, introducing logos and colour schemes which were essentially variants of the British Rail brand. Eventually, as sectorisation developed into a prelude to privatisation, the unified British Rail brand disappeared, with the notable exception of the Double Arrow symbol, which has survived to this day and serves as a generic trademark to denote railway services across Great Britain. The BR Corporate Identity Manual is noted as a piece of British design history and there are plans for it to be re-published.

Finances

Despite its nationalisation in 1947 "as one of the 'commanding heights' of the economy", according to some sources British Rail was not profitable for most (if not all) of its history. Newspapers reported that as recently as the 1990s, public rail subsidy was counted as profit; as early as 1961, British Railways were losing £300,000 a day.[39]

Although the company was considered the sole public-transport option in many rural areas, the Beeching cuts made buses the only public transport available in some rural areas. Despite increases in traffic congestion and road fuel prices beginning to rise in the 1990s, British Rail remained unprofitable. Following sectorisation, InterCity became profitable. InterCity became one of Britain's top 150 companies, providing city centre to city centre travel across the nation from Aberdeen and Inverness in the north, to Poole and Penzance in the south.

Investment

In 1979 the incoming Conservative Government led by Margaret Thatcher was viewed as anti-railway, and did not want to commit public money to the railways. However, British Rail was allowed to spend its own money with government approval. This led to a number of electrification projects being given the go-ahead, including the East Coast Main Line, the spur from Doncaster to Leeds, and the lines in East Anglia out of London Liverpool Street to Norwich and King's Lynn.

The list with approximate completion dates includes:

In the Southwest, the South West Main Line from Bournemouth to Weymouth was electrified along with other infill 750 V DC 3rd rail electrification in the south. In 1988, the line to Aberdare was reopened. A British Rail advertisement ("Britain's Railway", directed by Hugh Hudson) featured some of the best known railway structures in Britain, including the Forth Rail Bridge, Royal Albert Bridge, Glenfinnan Viaduct and London Paddington station. London Liverpool Street station was rebuilt, opened by Queen Elizabeth II, and a new station was constructed at Stansted Airport in 1991. The following year, the Maesteg line was reopened. In 1988, the Windsor Link Line, Manchester was constructed and has proven to be an important piece of infrastructure.

Privatisation

Privatisation of British Rail and Impact of the privatisation of British Rail

In 1989, the narrow-gauge Vale of Rheidol Railway was preserved, becoming the first part of British Rail to be privatised. Between 1994 and 1997, British Rail was privatised. Ownership of the track and infrastructure passed to Railtrack on 1 April 1994. Passenger operations were later franchised to 25 private-sector operators. Of the six freight companies, five were sold to Wisconsin Central to form EWS while Freightliner was sold in a management buyout.

The Waterloo & City line, part of Network SouthEast, was not included in the privatisation and was transferred to London Underground in April 1994. The remaining obligations of British Rail were transferred to BRB (Residuary) Limited.

The privatisation, proposed by the Conservative government in 1992, was opposed by the Labour Party and the rail unions. Although Labour initially proposed to reverse privatisation, the New Labour manifesto of 1997 instead opposed Conservative plans to privatise the London Underground. Rail unions have historically opposed privatisation, but former Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen general secretary Lew Adams moved to work for Virgin Rail Group, and said on a 2004 radio phone-in programme: "All the time it was in the public sector, all we got were cuts, cuts, cuts. And today there are more members in the trade union, more train drivers, and more trains running. The reality is that it worked, we’ve protected jobs, and we got more jobs.

British Rail Engineering Limited

Incorporated on 31 October 1969, British Rail Engineering Limited (BREL) was a wholly owned railway systems engineering subsidiary of the British Railways Board. Created through the Transport Act 1968, to manage BR's thirteen workshops, it replaced the British Rail Workshops Division which had existed since 1948. The works managed by BREL were Ashford, Crewe, Derby Locomotive Works, Derby Litchurch Lane, Doncaster, Eastleigh, Glasgow, Horwich Foundry, Shildon, Swindon, Temple Mills, Wolverton and York. BREL began trading in January 1970. In 1989 BREL was sold to a consortium of Asea Brown Boveri and Trafalgar House.

British Railways Mark 2

A family of railway carriages, designed and built by British Rail workshops (from 1969 British Rail Engineering Limited) between 1964 and 1975. They were of steel construction.

Advanced Passenger Train

In the 1970s, British Rail developed tilting train technology in the Advanced Passenger Train; there had been earlier experiments and prototypes in other countries, notably Italy. The objective of the tilt was to minimise the discomfort to passengers caused by taking the curves of the West Coast Main Line at high speed. The APT also had hydrokinetic brakes, which enabled the train to stop from 150 mph within existing signal spacings.

The introduction into service of the Advanced Passenger Train was to be a three-stage project. Phase 1, the development of an experimental APT (APT-E), was completed. This used a gas turbine-electric locomotive, the only multiple unit so powered that was used by British Rail. It was formed of two power cars (numbers PC1 and PC2), initially with nothing between them and later, two trailer cars (TC1 and TC2). The cars were made of aluminium to reduce the weight of the unit and were articulated. The gas turbine was dropped from development, due to excessive noise and the high fuel costs of the late 1970s. The APT-E first ran on 25 July 1971. The train drivers' union, ASLEF, black-listed the train due to its use of a single driver. The train was moved to Derby (with the aid of a locomotive inspector). This triggered a one-day strike by ASLEF that cost BR more than the research budget for the entire year.

Phase 2, the introduction of three prototype trains (APT-P) into revenue service on the Glasgow – London Euston route, did occur. Originally, there were to have been eight APT-P sets running, with minimal differences between them and the main fleet. However, financial constraints lead to only three being authorised, after two years of discussion by the British Railways Board. The cost was split equally between the Board and the Ministry of Transport. After these delays, considerable pressure grew to put the APT-P into revenue-service before they were fully ready. This inevitably lead to high-profile failures as a result of technical problems.

These failures led to the trains being withdrawn from service while the problems were ironed out. However, by this time, managerial and political support had evaporated. Consequently, phase 3, the introduction of the Squadron fleet (APT-S), did not occur, and the project was ended in 1982.

Although the APT never properly entered service, the experience gained enabled the construction of other high-speed trains. The APT powercar technology was imported without the tilt into the design of the Class 91 locomotives, and the tilting technology was incorporated into Italian State Railway's Pendolino trains, which first entered service in 1987.

InterCity 125

The InterCity 125, or High Speed Train, was a diesel-powered passenger train built by British Rail Engineering Limited between 1975 and 1982 that was credited with saving British Rail. Each set is made up of two Class 43 power cars, one at each end and four to nine Mark 3 carriages. The name is derived from its top operational speed of 125 mph (201 km/h).

The prototype InterCity 125 (power cars 43000 and 43001) set the world speed record for diesel traction at 143.2 mph (230.5 km/h) on 12 June 1973. This was succeeded by a production set reaching 148.5 mph (239.0 km/h) in November 1987

Successor companies

History of rail transport in Great Britain 1995 to date, Privatisation of British Rail, and Impact of the privatisation of British Rail

Under the process of British Rail's privatisation, operations were split into 125 companies between 1994 and 1997. The ownership and operation of the infrastructure of the railway system was taken over by Railtrack. The Telecomms infrastructure and British Rail Telecommunications was sold to Racal, which in turn was sold to Global Crossing and merged with Thales Group.[69] The rolling stock was transferred to three private rolling stock companies (ROSCOs); Angel Trains, Eversholt Rail Group and Porterbrook. Passenger services were divided into 25 operating companies, which were let on a franchise basis for a set period, whilst freight services were sold off completely. Dozens of smaller engineering and maintenance companies were also created and sold off.

British Rail's passenger services came to an end upon the franchising of ScotRail with the last service being a Caledonian Sleeper service from Glasgow and Edinburgh to London on 31 March 1997. The final service it operated was a Railfreight Distribution freight train from Dollands Moor to Wembley on 20 November 1997. The British Railways Board continued in existence as a corporation until early 2001, when it was replaced by the Strategic Rail Authority as part of the implementation of the Transport Act 2000.

The original passenger franchisees were:

Future

Renationalisation of British Rail

Since privatisation, many groups have campaigned for the renationalisation of British Rail, most notably 'Bring Back British Rail'. Various interested parties also have views on the privatisation of British Rail.

The renationalisation of the railways of Britain continues to have popular support. Polls in 2012 and 2013 showed 70% and 66% support for renationalisation, respectively.

Due to rail franchises lasting sometimes over a decade, full renationalisation would take years unless compensation was paid to terminate contracts early.

When the infrastructure-owning company Railtrack ceased trading in 2002, the Labour government set up the not-for-dividend company Network Rail to take over the duties rather than renationalise this part of the network. However, in September 2014, Network Rail was reclassified as a central government body, adding around £34 billion to public sector net debt. This reclassification had been requested by the Office for Budget Responsibility to comply with pan-European accounting standard ESA10.

The Green party has committed to bringing the railways 'back into public ownership' and has maintained this impetus when other parties argued to maintain the status quo. In 2016, Green MP, Caroline Lucas, put forward a Bill that would have seen the rail network fall back into public ownership step by step, as franchises come up for expiry.

In 2021 the government announced it would take back responsibility for the operations of passenger services through Great British Railways with service provision to be contracted to private operators.